Around the turn of the last century, Carol Norton was among the most widely known Christian Scientists. He was born in Eastport, Maine, in 1869, raised a Unitarian, and was related to the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He lost both parents when still a boy and moved to New York City to live with an aunt and uncle. After struggling with a longstanding physical difficulty that medical treatment failed to cure, he turned to Christian Science, which healed him after the first treatment. He wrote of this healing: “I could hardly realize it….Life to me now had a new meaning….The revelation was indescribable.”1

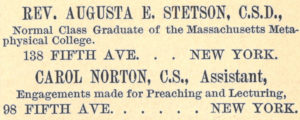

By this time, Carol had established a successful business career but gave it up to devote himself full time to the practice of Christian Science. A gifted writer and speaker, he became an assistant to Augusta Stetson, a student of Mary Baker Eddy who was at that time pastor of what was to become First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, and principal of the New York City Christian Science Institute. Carol’s name first appeared in The Christian Science Journal of February 1891 as assistant to Mrs. Stetson.

From The Christian Science Journal, February 1891

From The Christian Science Journal, February 1891

Recognizing his talent and ability, Mrs. Stetson gave Carol opportunities to preach, lecture, and aid in the promotion of Christian Science. She even went so far as to seriously consider adopting him. However, Mrs. Eddy, whom Carol had met through Mrs. Stetson and with whom he established a regular correspondence, foresaw problems arising from Mrs. Stetson’s hold on her young protégé and warned him of her influence. Carol ultimately severed his connection with Mrs. Stetson as assistant teacher and as Second Reader of First Church, New York.

Mrs. Eddy greatly valued Carol’s talents, character, and spiritual receptivity. In 1898, she invited him to attend what was to be her last class, held in Concord, New Hampshire. That same year, she appointed him, at the age of 28, as one of the first five members of the Board of Lectureship. His lectures were often standing-room-only events, sometimes held in huge venues, such as New York’s Metropolitan Opera House and Carnegie Hall. Although over 3,000 attended the Carnegie Hall lecture, on December 18, 1898, only one New York newspaper covered the event. Less than six months later, however, Norton’s appearance at the Metropolitan Opera House, on May 28, 1899, was covered by every major newspaper in the city.

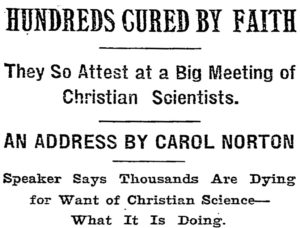

The New York Times, May 29, 1899

The New York Times, May 29, 1899

During this lecture, Norton reportedly asked all in the audience to stand who had been healed in Christian Science. Of the approximately 3,000 in attendance, about one-third arose and were acknowledged by “a great outburst of applause,” according to The New York Times.2

On April 2, 1901, Norton delivered the first formal lecture at a university – Cornell University, in Ithaca, New York.

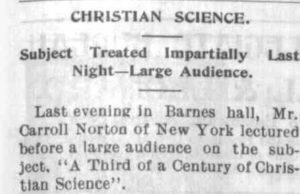

Cornell Daily Sun, April 3, 1901

Cornell Daily Sun, April 3, 1901

It was titled “A Third of a Century of Christian Science.”3 One noteworthy aspect of this lecture was Norton’s tribute to true womanhood – remarkable for a young man in any age but particularly so at a time when women couldn’t even vote. He said: “The present age witnesses woman’s ascension to her rightful place as man’s equal. The highest conception that man can have of the divine Being is to think of the infinite Motherhood of God as divine Love. Can it not then be truthfully said that ideal womanhood is the scientific expression of this phase of the divine Nature?”4

His discussion of “ideal womanhood” concluded with a loving tribute to the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science: “Mrs. Eddy is without doubt the greatest religious reformer of the nineteenth century and the greatest woman leader in the history of religion….To know her is to love her….Thousands upon thousands of men, women, and children offer up a perpetual Psalm of thanksgiving to the eternal Good for the great good that has come to humanity through the career of this God-governed woman”5

![“Elizabeth Norton, Longyear Museum, Chestnut Hill Massachusetts”]](https://daystarfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/05-Elizabeth-Norton-245x300.jpg) Elizabeth Norton (courtesy of Longyear Museum, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts)

Elizabeth Norton (courtesy of Longyear Museum, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts)

In April 1901, Carol Norton married Elizabeth Griffin of Boston. The couple lived in New York for another two or three years, then moved to Chicago, where, from this central location, Norton continued to serve the Church as a lecturer, traveling as far West as the Pacific Coast.

In 1904, Carol Norton was seriously injured in a trolley accident in Chicago. George Kinter, who was serving at the time as a secretary in Mrs. Eddy’s home in Concord, New Hampshire, received telegrams from Christian Scientists in Chicago, desiring to inform Mrs. Eddy as to what had happened. Mr. Kinter, however, was prevented from letting Mrs. Eddy know by the chief secretary (evidently Calvin Frye) who obdurately insisted on obedience to a rule that appeared between 1900 and 1910 on the editorial page of each issue of the Christian Science Sentinel. Around the time of this incident, it read: “The author of the Christian Science text-book takes no patients, does not consult on disease, nor read letters referring to these subjects.”6 Mr. Kinter felt that the rule should be disregarded in this case, but his co-worker was adamant. Telegrams continued to pour in, acknowledged only by the secretaries, and Carol Norton passed on unbeknownst to Mrs. Eddy.

Two weeks later, on hearing the sad news, Mrs. Eddy, according to Mr. Kinter, “…was moved to tears and literally wept copiously, exacting every detail and requiring to be shown all the telegrams….And now, how shall I convey any adequate sense of the pathos with which she appealed to me to ‘follow my own intuitions another time and let her know things like that, of such moment to our Cause,’ concluding with ‘Dear Carol, oh how I love him!’”7

Carol Norton’s passing occurred not long after he had finally broken with Mrs. Stetson. His “pure goodness,” in Mrs. Eddy’s words (see Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Trial, p. 298), perhaps never fully grasped the extent of Mrs. Stetson’s desire to dominate, although he apparently did come to see something of the dangers of her highly personal ambition. As mentioned earlier, Mrs. Eddy took special interest in Carol, giving him much private instruction, no doubt with a desire to ensure that he had a thorough understanding of Christian Science in its pure form.

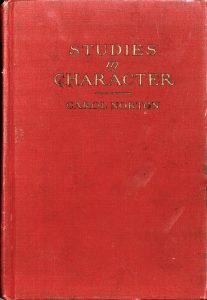

Carol Norton’s mark on the early Christian Science movement is indelible – as a practitioner, teacher, lecturer, church spokesman, writer, and poet. His posthumously published book Studies in Character, a series of articles, some of which originally appeared in the Christian Science periodicals, is a work of keen perception and tenderness – again, particularly remarkable for such a young man. Daystar Foundation reprinted this work some years ago, and it is still available through our gift shop and website.

Studies in Character (Daystar collection)

Studies in Character (Daystar collection)

There are some real gems in Studies in Character – deep insights into human nature and compassionate assurances of God’s care for those who obey His law. Here’s one of these gems, from an article included in the book, titled “The Lesson of Suffering”: “It is the inspiration and strength gained in life’s Gethsemanes that enables us to ascend our Calvary and bear our cross….Let not sorrow harden the heart nor quench love’s power in your life, but let it show the nothingness of existence apart from God’s own plan, and let it be the highway to the City of thy God.”8

Daystar also sells a reprint of a pamphlet by Mr. Norton – The Christian Science Church: Its Organization and Polity – which discusses the similarities between the primitive Christian church and the Christian Science Church as established by Mary Baker Eddy.

Elizabeth Norton left her mark on the movement as well. She became a practitioner and teacher of Christian Science, having been accepted in the Normal class in 1910 (taught by Bicknell Young), and continued teaching until 1943. However, she had been given the designation of C.S.B. back in 1906 by Mrs. Eddy, perhaps reflecting private instruction she received from the Leader herself. Acknowledging the conferring of this designation, Mrs. Norton wrote the following letter to Mrs. Eddy on Sept. 11, 1906, which was later published in the Christian Science Sentinel:

Beloved Leader and Teacher: – Please accept my most heartfelt thanks for the degree of C.S.B. which came yesterday. I could not express to you in words my appreciation for all your love and all you have done for me. When expressing gratitude as a child, it was always said to me, “Improve yourself and all the opportunities which are given you, and I shall be repaid.” So now, dear Leader, I am striving to live close to your teaching, praying for meekness, love, and purity, that I may heal the sick, bind up the broken-hearted, and give a correct sense of God’s chosen one. Carol’s little book [Studies in Character] came to me yesterday from the publisher, and I am sending you one by mail.

Thanking you again for the degree and all the opportunities which you have given me for progress, I am ever and always,

Your loving and grateful student,

Elizabeth Norton9

Mrs. Norton had first met Mrs. Eddy shortly after her husband’s passing, having been invited to Pleasant View. She later wrote of this experience:

On entering the room [Mrs. Eddy] extended her hand and asked me to be seated. I walked across the room and sat down in a chair. Mrs. Eddy very deliberately arranged her dress and sat down on a sofa. She looked at me so tenderly, and patting the sofa beside herself, she said, “You are too far away from Mother, darling.” I immediately went to her. She took me in her arms and kissed me. She was not afraid to express her love humanly, and I did not mistake it, for I learned then and there, that divine Love must be expressed humanly in order to heal the broken hearted.10

Perhaps this is the greatest legacy left by Elizabeth and Carol Norton and, indeed, by faithful pioneer Christian Scientists in general. It was a lesson learned from their Leader, who wrote in Science and Health: “The vital part, the heart and soul of Christian Science, is Love. Without this, the letter is but the dead body of Science, – pulseless, cold, inanimate.”11

Daystar has in its collection a number of books once owned by the Nortons, and several of them bear witness to this vital love – a love expressed touchingly by these early workers. The books date from around 1890 through the late 1930s. Following are some of the most noteworthy:

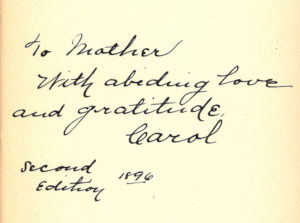

Inscription in Woman’s Cause (Daystar collection)

Inscription in Woman’s Cause (Daystar collection)

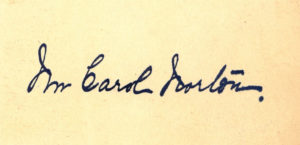

230th Edition of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures inscribed by Carol Norton (Daystar collection)

230th Edition of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures inscribed by Carol Norton (Daystar collection)

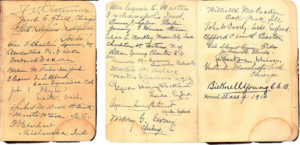

End pages from Science and Health signed by members and teacher of Normal class 1910 (Daystar collection)

End pages from Science and Health signed by members and teacher of Normal class 1910 (Daystar collection)

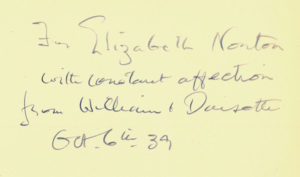

Inscription by William McKenzie in Christ My Refuge (Daystar collection)

Inscription by William McKenzie in Christ My Refuge (Daystar collection)

These books and others from the Norton collection may be viewed in an exhibit at Daystar Foundation and Library in Oklahoma City. We hope you’ll visit the library soon to view this and other exhibits, and to explore Daystar’s rich historical collection.

"*" indicates required fields